Three Critical Phases Of Formulation And Product Development

When Sarah Brown, founder of skincare brand Pai, couldn’t find a solution to her chronic urticaria, a condition that caused itchiness and hives on over 80% of her body, she created the remedy herself. “One of my main challenges was that this particular condition made me hyperreactive to all products,” said Brown. “I’d never had to think about what I put on my skin ever. I suddenly could put nothing on.”

In 2007, when Brown began her creating her product, the natural skincare market was underdeveloped and finding formulators was a difficult task. Brown was determined to make organic products that were also vegan and cruelty-free, and she tackled the formulation and product development process in her garage in West London. “I didn’t really have a business. I had six great products that I really believed in and I had formulated myself,” said Brown. To expand her line, she hired a former L’Oréal chemist who had a desire to work in the natural space.

Today, with celebrity fans like Natalie Portman and wide distribution in retailers such as Anthropologie, Free People, Neiman Marcus, Bloomingdale’s and Credo, the brand continues to formulate its own products in a 12,000-square-foot facility that produces upwards of 25,000 units per week. Brown shared her expertise and devotion to in-house production during Beauty Independent’s recent In Conversation webinar, the second of a five-part series on product development and commercialization sponsored by Cosmetic Solutions. She was joined Becca Anderson, director of education at Cosmetic Solutions, and Odalys Gonzalez, the manufacturer’s director of research and development.

Together, the webinar participants highlighted best practices for embarking on a formulation process, weighed the advantages and disadvantages of in-house and outsourced production, and delved into the steps and decisions beauty brands founders face. Here are key takeaways from their discussion.

PHASE ONE: ENGAGING A LAB

To cut down what may seem to be a daunting number of options, the formulation process starts by generating a formal product development request (PDR). Under the guidance of a formulator, the PDR is basically a wish list of dream product attributes. By establishing ideal guidelines for a brand’s future product, formulators are able to better grasp the holistic view of the item’s form, look, substance and performance. “Your formulation is your physical DNA of your brand,” said Gonzalez. “This will not only determine what you put on the market, but how the market receives your brand.”

When the PDR is finalized, each attribute is reviewed to determine whether the components are compatible with one another. This assessment helps the formulator identify potential trade-offs and efficiencies, and present them to the brand creator to accept or work on accommodations. “It’s a validation of the project,” said Gonzalez, explaining the negotiation and evaluation. “You should be able to discuss openly with your chemist what type of product you’re looking for, what type of claims you’re looking to make, what type of packaging you’re looking to use in this formula, what type of cost, and key ingredients that you want to use. You need to include on here also market regions, where do you want to sell. All of this information is essential for developing the formula quickly for the next phase of the formulation.”

Pro Tip: A PDR is more easily derived when there is a sturdy target product profile created in the market analysis phase. “The more information and the more accurate the PDR is the smoother the process will be,” said Gonzalez. “The turnaround times for submissions will be quicker.” Anderson chimed in, “Come prepared with a very robust target profile. Do your homework. We want to have a clear direction on where we’re going to live in the marketplace, what the pricing needs to be in order to make sense, and how we’re going to get there.”

PHASE TWO: FORMULATION AND TESTING

Behind formulation possibilities are decisions to be made about ingredients and ingredient sourcing. Chemists rely on product profiles to determine limitations and recommendations. This version of a draft formulation is the basis for what the professionals call a “bench formulation” or the actual, physical creation of the first rendition. Gonzalez said, “This is [what] the chemist enjoys, seeing the entire process coming together, going from a formula on a piece of paper to actual creation of a product.”

It’s Brown’s intense interest in this aspect of creation that compels her to keep Pai’s manufacturing in-house. “I passionately wanted to have oversight on how an ingredient was moving into our premises, how it was being stored, how it has been handled,” she said. “It [gives] us complete flexibility to test and learn.”

The formula may have to endure multiple iterations dependent on chemists’ opinions of the outcome. Gonzalez said, “They might do a couple more revisions within the lab until they get it perfect to meet all the requirements of that PDR.” The first viable lab sample is sent out for initial stability testing before reaching the client.

Beyond the lab, the testing phase involves client approval. It’s time to accumulate feedback on the product from a holistic perspective. Whether adjusting the fragrance level or amending a texture, viscosity or pH level, each minute adjustment means time revising the lab.

Once the product is approved, it formally heads to formula testing to verify stability. “We want to formulate so that we know that, when we send this product out for testing, it’s going to pass with flying colors,” said Anderson. She elaborated that stability and compatibility testing are crucial in determining whether the formula is durable and a good match for the selected packaging.

Pro Tip: “Take your time to evaluate and gather all the feedback. Maybe you [should] have more than one person evaluating with your team member or family members,” said Gonzalez. She encouraged brands to gather what they like—and don’t like—about the iteration prior to review with the chemist. Gonzalez said, “The more accurate your feedback, the less time it will take for a reformulation.”

PHASE THREE: GETTING TO MARKET

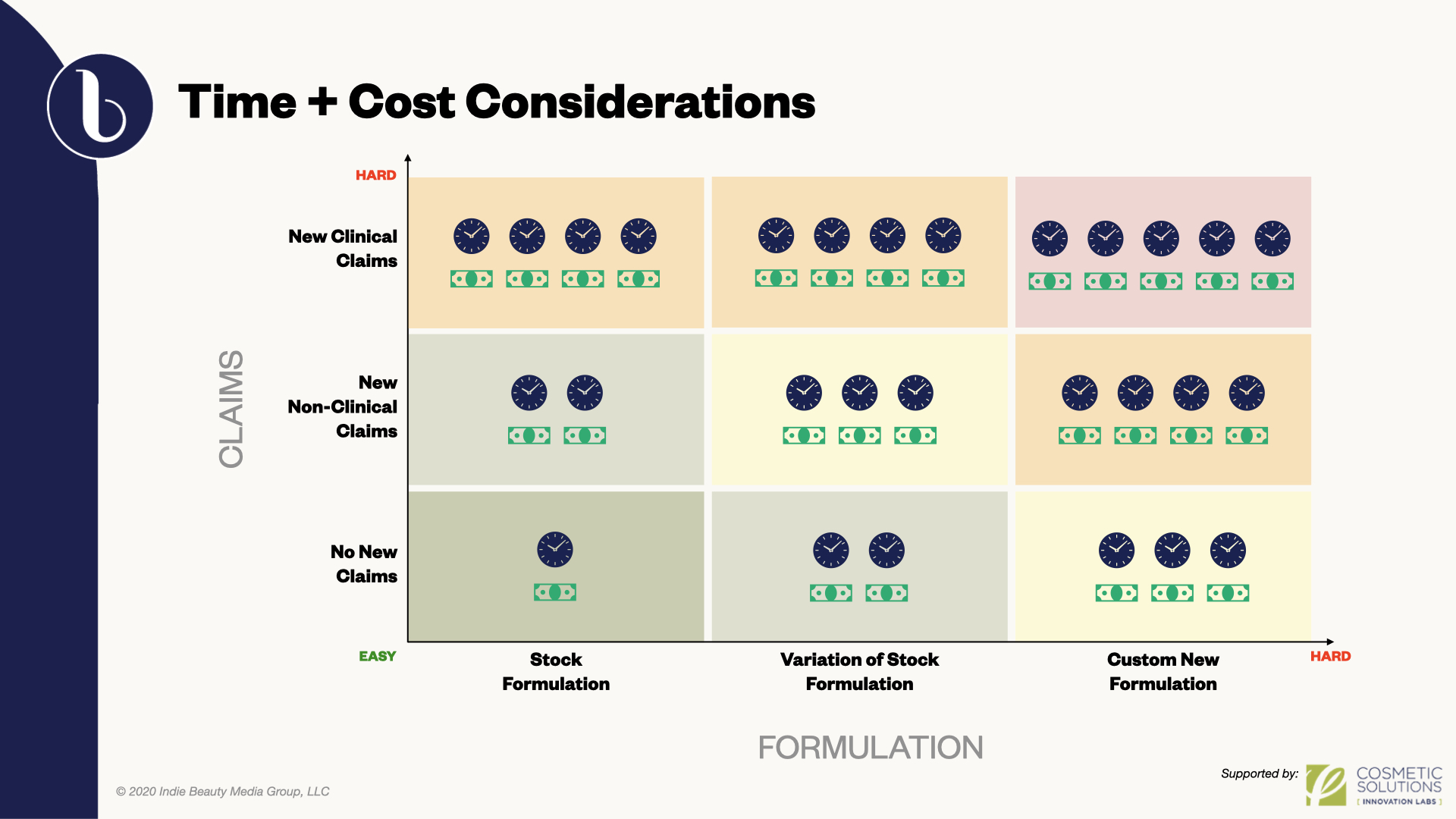

Depending on a brand’s budget and timeline, formulation can be selected out of a library of stock formulas or completely customized. Stock formulation allows speed to market. Claims associated with the formula are already validated. Custom formulas involve greater time for modifications and, if any new claims are being brought forth, they will have to be substantiated, particularly clinical claims. “These are things that, if you’re using it in your promotional material, you have to have the clinical data to support it,” said Anderson. “And doing those clinical trials based on your diagram seems to have an exponential effect on your time and development costs.”

“Cost of a formulation can vary immensely,” added Gonzalez. “So, take into consideration before you start, what is your budget, and how much time do you have? Obviously, the more time you have, the more custom your formulation can be, but it can also be very costly.”

Cost and time can be dependent on finding the right formulator. “Make sure that you find a formulator that’s very familiar with claims,” said Gonzalez. “Your formulator should know exactly what it is that you’re looking to claim on your product.” Whether a product is natural, vegan or making anti-aging, hydration or other claims, the key is to avoid unnecessary expense and lengthy revisions by focusing on the precise criteria generated by the brand.

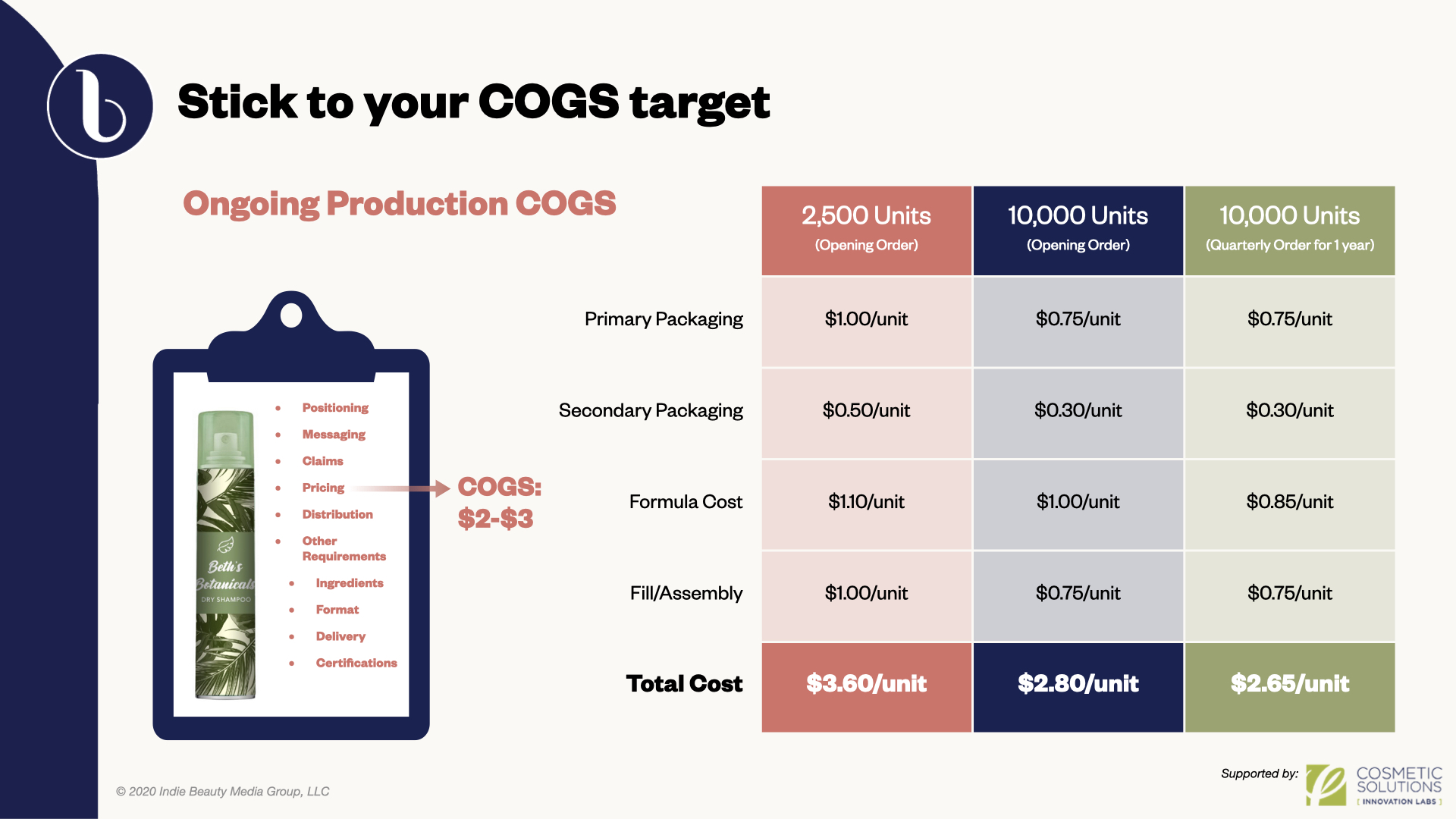

Anderson instructed brands know their cost of goods and have an understanding of their future distribution. She cautioned them to not enter the market too quickly without doing their homework. “As you start to gain traction in the marketplace, [you don’t want to] come back to square one and make that investment of time and money all over again to reformulate,” said Anderson. “Understand what these numbers need to look like for your business model and understand where you can flex in order to make it all make sense in the end.”

Pro Tip: Brands should secure a facility that can scale with their businesses. “You want to be able to reproduce that formula that you fell in love with at a larger quantity and, believe it or not, sometimes that can be a problem with certain facilities,” said Gonzalez. She urged brands to look into whether they can produce larger batches and how quickly they’re able to generate products in a restock situation. Anderson said, “Get to know the volumes of your business and that they really match the sweet spot of your manufacturer.”

On the in-house manufacturing side, Brown described equipment that can cost over $1 million to acquire and her commitment to managing a team of 63. “You don’t do this unless you’re really passionate about manufacturing,” she said. Brown is transparent about downsides. “It’s a lot of inventory to hold,” she said. “That eats up cash, and [it’s] more risk really because you’ve just got to be so mindful of preservation, control and contamination.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.